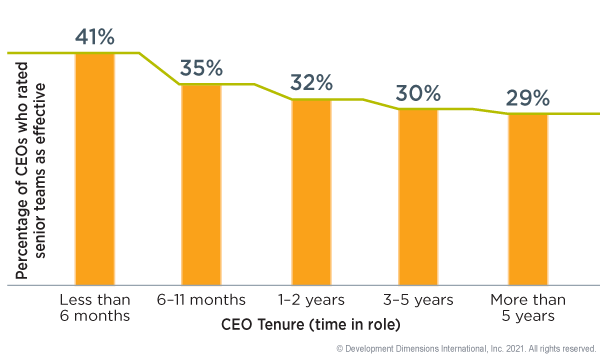

Effective executive teams are hard to come by, according to CEOs. In a new DDI study that asked CEOs to evaluate the strength of their senior teams, only 4 in 10 CEOs say their teams are “effective" or “very effective.” And these ratings peak during the first six months of a new CEO’s tenure, and progressively worsen across their first five years in role.

This data suggests that new CEOs come in optimistic about the effectiveness of their senior teams. But over time, they start to see the cracks: weaknesses, poor team dynamics, and lack of results. So how can senior teams get back on track? How can you tell if the team is delivering results right now and in the long-term? What skills do executive teams need to be successful?

In this blog, I’ll explore how to measure executive team effectiveness over time. I’ll share what my experience as an executive coach has taught me about the skills effective executive teams have and how these skills can be mastered.

Measuring Executive Team Effectiveness

To paraphrase the modern-day sage Forrest Gump, “Effective is as effective does.” Simply put, the success of an executive team can be measured by looking at whether it delivers outcomes while fostering a sustainable culture.

This involves setting direction and establishing the mechanisms that enable collaborative effort to achieve them. This also means addressing “Whats” and “Hows.” The notion of sustainability is important because the ultimate test of an executive leadership team is the ability to create long-term value, not just drive results in the next quarter.

Measuring the extent to which a senior team is delivering the “Whats” is relatively easy. Is the team hitting its quarterly objectives? Is there reason to believe that results will be delivered in the near term? (To answer this question, forecasts are a typical metric used.) Does the team have a longer-term track record of goal achievement?

Regarding that last question, many executive teams use a “balanced scorecard” to measure outcomes. And while some might argue that elements of a balanced scorecard are subjective, scorecard elements reflect “outcomes” that the team is accountable for delivering.

Assessing an executive team’s performance against the “Hows” is more difficult. Does the company have well-defined and efficient processes to translate its inputs into outputs? (Measures of operational efficiency give us some indication of this.) Does the company have a culture that aligns with and supports the organization’s mission and values?

Despite the generally accepted wisdom of management expert Peter Drucker that “culture eats strategy for breakfast,” these sorts of executive team effectiveness metrics are given lower priority. That is if they are considered at all.

Executives Must be Experts in Human Dynamics

My experience as an executive coach suggests that the challenges of managing “Whats” and “Hows” are not evenly distributed. Most of the C-level leaders I work with have a clear idea of the mission and direction of their organizations. They also have clear goals and objectives. And, for the most part, these goals are effectively cascaded down throughout their organizations. Very little of my time as a coach is spent helping clients establish strategies or set direction.

Most of my coaching work involves helping leaders influence stakeholders, implement efficient work processes (often referred to as “governance”), and manage culture. In one instance, a leader I work with is responsible for managing an organization-wide project to implement a new IT infrastructure. The goals of the initiative are clear. The challenge is getting numerous individuals and the departments they represent to partner together to define processes, implement new work systems, and sustain them over time. The greatest challenge to delivering the initiative successfully involves managing the human dynamics of the work, not the technical requirements.

In another instance, a leader is working to enhance his organization’s ability to adapt to new customer requirements while improving operational efficiencies. The organization’s performance metrics are clear (revenue, margins, and customer satisfaction). But getting numerous department heads to break down a siloed culture and pull together to address these requirements is the nut that must be cracked.

I’m not saying that establishing strategic direction, effective decision making, and execution skills aren’t important. Executives and senior teams must individually and collectively possess these skills. But these are “table stakes.” Skills that differentiate the most successful leaders and teams are those that involve human dynamics: building networks and partnerships, influencing, navigating politics, and personal growth.

Effective Executive Teams Master Necessary Skills Collectively

How executive and senior teams master these requirements takes many forms. For example, sometimes executives on a team are all highly skilled in these areas, while other times, team members bring complementary skills. My experience suggests that leaders need at least a modicum of each of these. But it’s likely that there will be some differences across the team on these dimensions.

The most important point is that teams understand their collective requirement and figure out how to deliver on it. Either create a team where all members share these strengths or rely on the team members to have these strengths to drive the team forward. Either way, the team needs to collectively demonstrate these capabilities.

Having team members understand their own strengths and weaknesses helps. But it also helps to have an appreciation for the strengths and skills of other leaders. When leaders have this, they can steer decisions, encourage input, and weigh the contributions of team members to help guide the team to appropriate actions.

The Human Dynamics of Executive Teams

Up to this point, I’ve focused on how senior executives impact the teams they lead. But the human dynamics skills I’ve highlighted need to be applied to the executive team itself because executive teams involve some unique challenges.

Let’s go back to the research I mentioned earlier about how CEOs’ confidence in their teams' performance declines over time. At first glance, this result is surprising. You would expect the longer a team works together, the more effective it would become. The team’s purpose would be clear, processes would be honed, communication should be automatic, and team member cohesion would be high. Right?

But a deeper understanding of the human dynamics of senior teams might help explain these results. In many of my executive coaching engagements, I’ve had the opportunity to assess the personality characteristics of senior leaders. I’ve found one common factor: high ambition. You don’t generally get to be a senior leader unless you have the drive and competitive spirit necessary to overcome difficult challenges and achieve outsized results. These leaders also typically have a strong personal growth orientation.

It doesn’t take much imagination to see what might happen when you bring a bunch of leaders with high ambition together onto a senior team. Where is their next promotion? If the existing CEO plans to stay on, the possibility for upward movement for the other team members is blocked.

Opportunities for personal growth can also be stymied as these leaders put their efforts into developing their subordinates and junior team members, while focusing less attention on their own development. Over time, this may lead to stagnation, frustration, and, in a worst-case scenario, intra-team competition.

Insights from Looking at the Life Cycle of Executive Teams

My experience working with teams over the past 35 years suggests that teams, and especially executive teams, have a “life cycle.” The notion of a “life cycle” is familiar to anyone who’s studied the life sciences. Living organisms go through a predictable process of formation, growth, stagnation/decline, and death (or transformation). Teams can be thought of as living organisms that are driven by human dynamics.

Viewing executive teams through this lens provides insights into actions that can be taken to sustain effective executive teams over time. Much has been written about how to support executive team formation and growth, but senior leaders have been provided with less guidance to prevent stagnation and decline.

Leaders need to look for signs of disengagement and stagnation. (As a coach, I can attest to the fact that this is a real issue for many senior leaders with long tenure.) Executives, just like others in the organization, need challenges to continue their development and fulfill personal growth needs.

The competitive instincts of senior leadership team members must also be addressed. This may involve opportunities to expand into new business ventures, lead business revitalization efforts, or develop new products. While some of these activities may lead to promotion opportunities, such as heading a new venture, the key is to provide executives with an outlet for their ambition that meets both organizational and personal needs.

The Key to Effective Executive Teams

No two executive teams are alike—they are comprised of unique individuals with a complex matrix of skills and personality traits. The common thread is that they establish objectives and bring people together to achieve them.

They must be, individually and collectively, master managers of human dynamics. And this mastery is nowhere more important than when it’s applied to the formation and maintenance of the executive team itself.

To learn more, watch our on-demand webinar: What Your Board Needs to Know About C-suite Development

Jim Thomas, Ph.D., is an executive consultant at DDI. He has more than 35 years of consulting experience in leadership development and talent assessment in the U.S. and internationally. This includes extensive experience developing and coaching executives and senior teams from many different industries and diverse backgrounds.

Topics covered in this blog