Vulnerable leadership wasn’t exactly part of the culture for one automotive parts manufacturing company I worked with. Among the executives I was coaching, there wasn’t much value for emotional sensitivity. That’s not to say they were unpleasant people.

Rather, they felt the weight of responsibility on their shoulders. In their eyes, the best way they could support their teams was to have all the answers. After all, that’s why they got paid the big bucks.

But one executive encountered a challenge so big that he didn’t know what to do. After a round of cost-saving measures, he had cut his team’s spending to the bone.

And then he got hit with a mandate from the CEO: He had to cut another $8 million from the budget. Short of laying off a lot of people—which would make it even harder to get the work done—he had no idea what to do.

So in a rare moment of vulnerability, he took the problem to his team of lower-level executives. And for the first time, he said, “I need your help. I don’t know what to do here.” They got to work immediately.

In the end, his team didn’t just find $8 million in cost savings. They found double.

And they didn’t lay off a single person.

It was a light bulb moment for the executive. When he thought he was at his weakest, he was actually leading at his strongest. And it changed the dynamic on his team permanently. They suddenly started working together much closer to solve problems and to help one another to reach larger goals.

It turned out that vulnerability could actually pay off—big.

What Is Vulnerable Leadership?

The idea of vulnerable leadership has been around for a long time. I’ve seen everything from the wildly successful TED Talk from Brené Brown on the Power of Vulnerability to a host of books on the topic—like my favorite, The Culture Code by Dan Coyle. I’ve even seen some really nice models, like Jacob Morgan’s Vulnerable Leader Equation (side note: we collaborated with Jacob on some exciting research about vulnerable leadership, which will be covered in his upcoming book).

These are all great sources, and I highly recommend going further into the research behind vulnerability and its connection to great leadership.

But for practical purposes, I’ll give you a really simple definition: For executives, vulnerable leadership is having the courage to admit their flaws and challenges with their teams. It’s about being able to say, “I don’t know, or I’m not sure. I need help with this.”

It might sound overly simple. And most executives would probably tell you they already do this. They will tell you they already are their authentic selves at work.

But this is a key point that executive coaches should really press: When was the last time you really said you didn’t know? When did you say I need more help to figure out the solution?

More often than not, executives struggle to come up with a clear example. Because while they think they’re doing it, they aren’t really. Because vulnerability is incredibly hard to practice.

Executives Like the Idea of Vulnerability. But They Don’t Do It.

As the idea of vulnerable leadership has grown in popularity, a lot of executives say they like the idea. At least, they like it when it comes to other people showing vulnerability. But when you ask them to do it, it’s a whole different story.

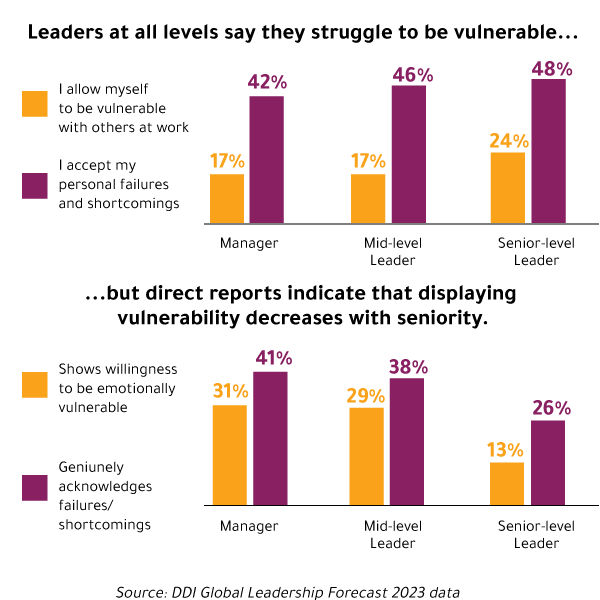

According to our Global Leadership Forecast research, 24% of senior leaders say they allow themselves to be vulnerable with others at work. And 48% say they accept their personal failures and shortcomings.

But their direct reports tell a different story. Only 13% of leaders who report to senior executives say those executives are willing to be vulnerable, and 26% say those senior executives genuinely acknowledge their own failures and shortcomings.

Meanwhile, leaders at lower levels of the organization are more likely to say they struggle with these ideas, but their direct reports say they demonstrate vulnerability on a much more regular basis.

The data is very clear that a shift takes place when people get into executive roles. They become more aware of the concept of vulnerability in leadership and seem to happily give lip service to the idea. But they aren’t actually doing it.

Why Vulnerability Is So Hard for Executives

As part of one of my executive coaching engagements, I asked the HR person who I was working with why she thought her executives were struggling so much to show vulnerability. She rolled her eyes: “Two parts ego and one part fear of not having the answer or being right. Everyone is trying to be the smartest person in the room.”

My HR friend wasn’t wrong exactly. Ego is a major barrier to expressing vulnerability. But it’s often misunderstood. We often assume that it means that the person is exceptionally arrogant and can’t imagine that they could be wrong. While I’ve met a few executives like this in my career, it’s rare.

Rather, more people are like one COO I coached. He had major imposter syndrome. He came close to experiencing panic attacks because he was afraid of being “found out” that he wasn’t qualified. (In reality, he was one of the most qualified executives I’ve ever worked with.) But he was convinced that if he ever said, “I don’t know,” it would be the ammunition the company needed to send him packing. Worse, then he’d have to admit to his friends and family that he was a failure.

Not all executives have imposter syndrome, but many are driven by the same motivation as the COO: Fear. Fear that they will fail. Fear that they will be perceived as incompetent. Fear that others will think less of them.

Often, executives have advanced to their position by having all the right answers. And in many cases, they really are the smartest person in the room. But it becomes the only way they know to succeed. They think, “If I don’t have all the right answers, what’s my value here?”

That’s where ego comes in. They aren’t trying to be perfect because they think they are perfect. They are avoiding vulnerability because they think if they make a mistake or admit a weakness, it conflicts with how they see themselves and the value they provide to the organization.

Ironically, however, the lack of vulnerability may in fact be the thing that most inhibits their success.

Does Showing Vulnerability Undermine Trust?

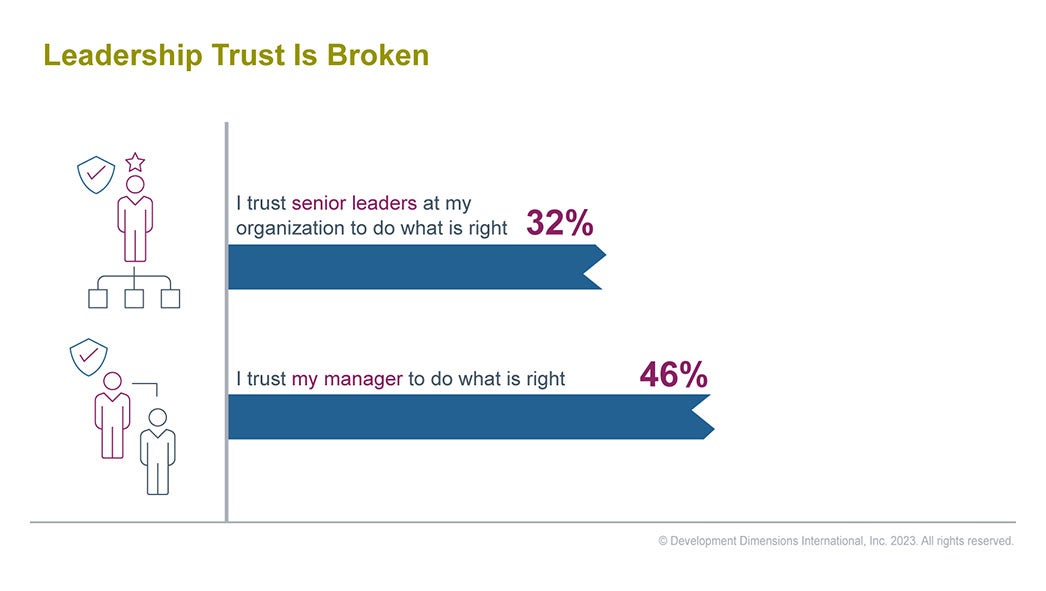

When I talk with executives about vulnerability, one of the common worries is that they will lose the faith and trust of their team. If they reveal that they don’t have all the answers, how will anyone trust them to lead the company’s most critical strategies?

On the one hand, they are right to be concerned about a lack of trust. According to DDI’s Global Leadership Forecast 2023, only 32% of leaders say they trust senior leaders in their organization.

But the research also showed that employees are 5.3X more likely to trust their leaders if they regularly show vulnerability. And employees were 7.5X more likely to trust leaders who genuinely acknowledge their own failures and shortcomings.

Why? Because by showing vulnerability, leaders invite others into the process of finding answers. They create an environment of “psychological safety” in which people feel safe to express their ideas, without fear of embarrassment or failure. As Daniel Coyle documented in his book The Culture Code, extensive research shows that an environment of psychological safety is the crucial ingredient that all high-performing teams share.

A Lack of Personal Vulnerability Creates Business Vulnerability

While some executives eventually buy into the idea that vulnerability with their team can boost performance and problem solving, they often have a harder time showing vulnerability to the high-ranking executives above them or, for those at the very top, the board.

However, this lack of vulnerability leads to one very big problem: Executives avoid solving the most critical problems. Instead, they focus completely on what they know how to do and avoid talking about the things they don’t know how to solve.

Recently, I saw this happen with a CEO of a multinational manufacturing firm. The guy was brilliant— easily the smartest guy in any room.

But he had a big challenge on his hands. While the company was headquartered in the U.S., most of its operations were spread across Asia. The relationship between the employees based in the U.S. and those in Asia was contentious, resulting in high turnover.

The CEO had no idea how to solve the problem. Instead of admitting how badly he needed help, he focused on solving challenges he was more familiar with. Repeatedly, he dodged the board’s questions about turnover, hoping the issues would resolve if he fixed other problems in the business. But they didn’t, and he was eventually replaced after a long period of underperformance.

Unfortunately, this CEO’s story is common. And it’s relatable: Many of us avoid dealing with things that make us uncomfortable or where we have little understanding. But when this human tendency to avoid personal vulnerability occurs in executives who make critical decisions, it opens up massive vulnerability for the company.

What Does an Appropriate Level of Vulnerability Look Like in Executives?

As with most things, vulnerability is best done in moderation. But a lot of leaders aren’t really clear on what it looks like to express vulnerability appropriately. How much is too much? What level isn’t enough?

So let’s start with some clarity on what vulnerability is NOT:

- A lack of confidence: “I have no idea what I’m doing.”

- A pessimistic attitude: “I don’t see how we could possibly do that.”

- Being too self-deprecating: “I’m a total idiot when it comes to technology.”

Instead, here’s what it does sound like:

- “I’m not sure how we’ll accomplish this, but between all of us, I’m certain we can find the right solutions.”

- “This is new terrain for me, we’re going to have to do some learning together.”

- “You (individual or group) are the subject matter experts here, so I’m looking to learn from you and tap into that expertise to help lead us in the right direction.”

- “When I was first in (a previous role), I was clueless, and this is how I managed the situation to eventually transition to feeling capable.”

You might also hear phrases like “I’m having trouble,” “I’m stuck,” or “I could be wrong here—what do you think?” In short, leaders are not limited to their own thought processes. They focus on using language that enables people to come forward with their wildest ideas.

How to Develop Vulnerable Leadership in Your Executives

It’s unlikely any HR professional expects to walk into a room of executives and tell them they all need to become more vulnerable.

Rather, vulnerability is something that can be woven into a larger executive development approach. Here are some of the tactics we’ve used with our clients to help executives become more comfortable with vulnerability:

Leverage 360 data:

If you’re collecting 360 degree feedback with your executives, include some questions about how others perceive their approach to unfamiliar situations. Do they ask for help? Do they work to collaborate? Do they seek to learn from others when they don’t have expertise in a particular area? The 360 can help the executive understand how others view them, and if it aligns with their intentions.

Employ personality assessments:

Personality assessments with feedback from a trained feedback provider can help give executives those “a-ha!” moments about why they react the way they do in certain situations. The assessment can also be used later by an executive coach to help leaders understand their natural tendencies to avoid vulnerability and how the consequences may be playing out in their work. A note of caution: You should be careful to use the right personality assessment, especially as you’re working with executives. They need data that reflects the nuance of their role. At this level, it will not be helpful to use personality tools that are too simplistic or focus on simply categorizing people into personality groups.

Go deeper with executive coaching:

An executive coach can employ a few tactics (questioning, role-playing, feedback, etc.) to help executives become more comfortable demonstrating vulnerability by focusing on behaviors that signal humility, inclusion, and authenticity. The coach can also help them recognize how the words they choose (as I detailed in the section above) either help or hinder their efforts to practice vulnerable leadership.

You Have to Build a Culture of Vulnerable Leadership

The biggest barrier to vulnerable leadership is your leadership culture. It has to be a shared value that starts at the top. Or else it becomes the unproductive, cutthroat culture that every executive fears, in which any admission that you don’t have all the answers becomes a threat to your career.

But when your executive teams embrace vulnerability, you’ll see a shift in your culture. Like the executive I described at the beginning of this piece who doubled the expectations on cost savings, you’ll see teams start to achieve more than you might have thought possible. More importantly, executives will be better able to engage their teams to solve the big, hairy problems that are most critical to the business.

All that strength can come from a single moment of truth, when someone in a position of strength admits weakness.

As Margaret Wheatley—a writer and leadership activist—once said: “We become hopeful when someone tells us the truth.”

Learn more about DDI executive coaching.

Richmond Fourmy, Psy.D., is an executive consultant with DDI, focusing on CEO succession and leader development for national and global companies. Richmond is a clinical psychologist who started out in the psychotherapy world, before moving to the corporate sector 27 years ago. He has consulted to and coached senior leaders across multiple industries, and he considers himself fortunate that his clients have asked him to travel to five continents and countless countries. When he’s not pursuing his passion for live music, Richmond can often be found standing in a river fly-fishing or wandering the Blue Ridge Mountains searching for the perfect view.

Topics covered in this blog